Living with our (pre)histories

Notes inspired by Scott’s ‘Against the Grain’ as part of a reading circle on Deep Histories of Landwork.

— From Avi (Dr. KBH)

Once upon a time, there were simple hunter gatherers who survived day-to-day. Then someone invented agriculture and humans became farmers. Farming allowed humans to become sedentary, store grains and accumulate a surplus. This enabled humans to urbanise, build cities and create states. Civilisation was born. Rulers were also born to protect this social evolution of complex civilization and make sure it progressed in an orderly fashion.

The first implication of this story is that one should take it as normal that ‘the best’ and ‘most talented’ naturally lead the rest of us. After all, it is for our own benefit and the greater good that they maintain civilized order. I mean, why else would some people ‘succeed’ and ‘hold power’? Even if those vested with this power often abuse it. The second implication is that inequalities are to be expected, since the progress of civilisation is incomplete. In short, ‘we’ just need to keep improving policies and do our little bit to keep moving forward step by step, stage by stage to try and mitigate the inherent inequality of living in a complex society.

So, the story goes.

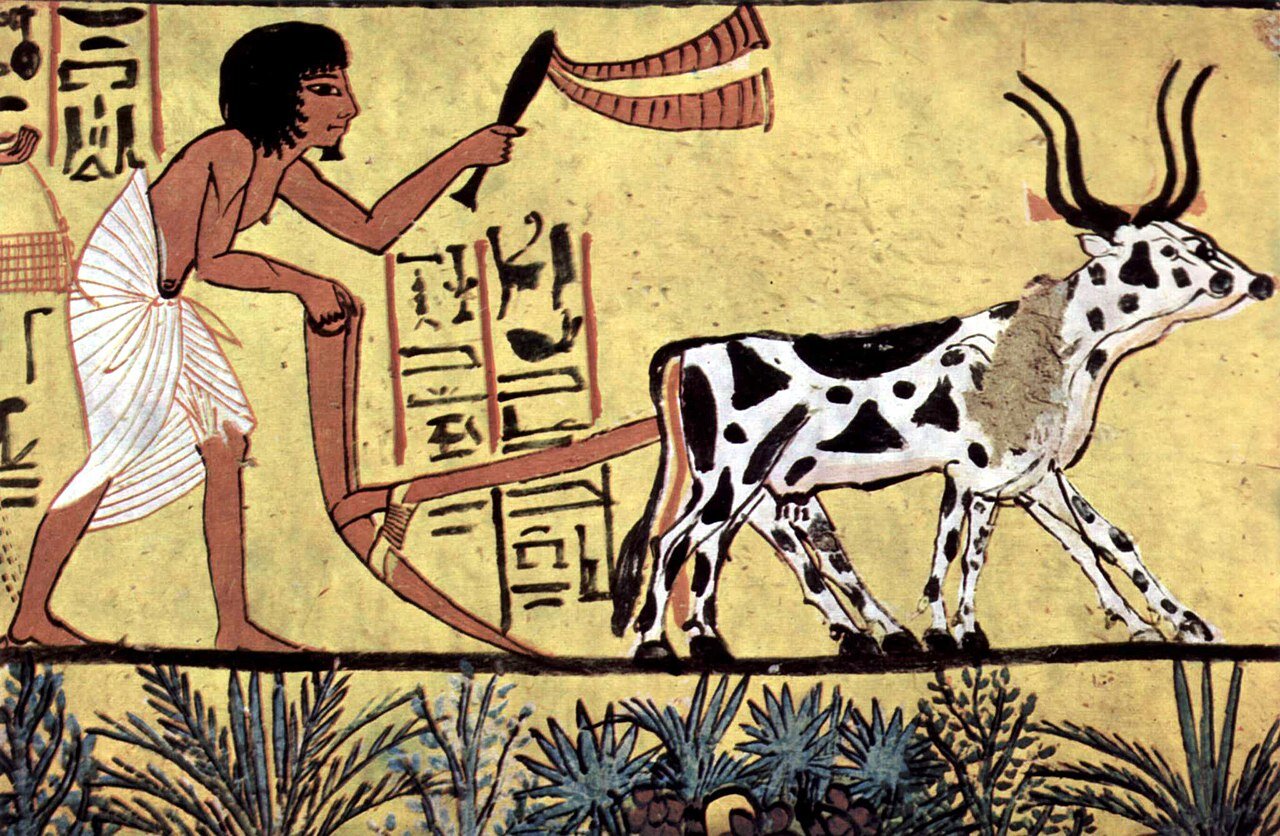

The idea of the Agricultural Revolution is a key building block in this narrative. It is the part that tells us that the transition from simple hunter-gatherers to complex hierarchical societies, via sedentism and the irrigation of land by early states, was catalysed by the invention of agriculture. Against the Grain by James C Scott is an accessible book that brings together a selection of archaeological research that debunks this just-so-story. If you haven’t heard about this revolution in archaeology, Scott is here to solve that — To explain the archaeology of prehistory.

Scott draws on empirical data to show that sedentism predated agriculture and that, contrary to the idea of the agricultural revolution, early states irrigated land for farming. Agriculture had its origins in wetlands and their drainage, not irrigation of dry land. Why does that matter? A key pillar of the idea of an agricultural revolution is that the state is needed because it can organize irrigation to supply a large urban population with food. Scott by contrast demonstrates that the alluvial wetlands of rivers were teeming with diverse possibilities for food to feed civilizations without the need for a grain-based agriculture. However, emerging states needed taxable (easily appropriable, storable and measurable) goods to sustain elites and their underlings. So, wetlands were drained to enable the growing of foods that fulfilled these requirements: cereal grains.

Take another pillar that props up the idea of the agricultural revolution — that agriculture leads to secured food storage upon which you can then build an urban civilisation. Scott demonstrates that it is in fact riskier, and it had a less resilient storage capacity than the use of a mix of hunting, foraging, fishing, gathering, cultivation and agricultural techniques. In essence, with the appropriate knowledge, ‘nature’ acted as a more secure and fruitful living food store but was less controllable than grain stores based on sedentary agriculture. Scott continues, upturning bit by bit the agricultural revolution and the wider narrative that rests on it. The point being that agriculture and the state elites that controlled it were not relied upon to supply people with food, but instead those leaders developed agriculture to sustain themselves and the social hierarchy they depended on.

For me, the book speaks to an appreciation of (pre)history as multidimensional, complex and dynamic, where different groups of people experimented with different food systems in different ways. At the same time, highlighting how ‘the state’ emerged, not as a given or a stage of progress, but as a unique combination of coercive social structure and disease-ridden food system. In addition, Scott illustrates how ‘the state’ was not a superior or inevitable stage in development that can be isolated from other forms of living taking place as a ‘lesser stage’ of social evolution.

For example, he summarises the symbiotic relationship that emerged between ‘barbarians’ and early states, rather than seeing them as different stages of society. Think of what you may know about Vikings; barbarians who raided states. What is sometimes less obvious is that they also trafficked in free peoples they enslaved, to trade with states. The just-so-story, of which the agricultural revolution idea is a key part, would have you believe that the state is the pinnacle, the barbarian society one stage behind and everyone else some sort of primitive. Basically, a grotesque literalised reading of slavery routes as pipelines of social evolution.

This reading of Scott also provokes the idea of state building as some sort of (pre)historic process of gentrification, whereby powerful barbarian groups acted as a conduit for the extension of state empire. In some sense, this is similar to the way some organisations today gentrify ‘nature’ and its inhabitants through ethical consumption, green tourism and creating protected or ‘rewilded’ areas. At the same time, transforming the previous ‘primitive’ inhabitants into poor or dependent subjects.

In sum, (pre)history, like any story, is empirically non-reducible to a singular causal chain of historical events, including the bogus idea of the agricultural revolution. However, this reduction occurs anyway as part of an ego/ethnocentric means of justifying today’s status quo as the pinnacle of human achievement. Essentially, a way of seeing the status quo as a natural stage of a singular social evolution.

But the main question that arises for me in the wake of reading Scott’s book is: what is the point of understanding this birds-eye-view? I feel like there is something key missing. This is an especially pertinent question for me as I work, teach, read, and write about environmental management and public health, two fields that care for life and are imbricated in how we read (pre)histories. They also take a birds-eye-view in response to reductionist narratives, but I also feel like they are missing the same key thing that Scott does in this book.

Before I identify what I think is missing, let me elaborate on what I mean by birds-eye-view: I mean approaches that try to explain the world by sketching it out and summarising the many key factors that influence a particular outcome, while at the same time rejecting one clear causal arrow of progressive events. Therefore, the point of the birds-eye-view is to lay out empirical observations about a context as factors and the links between them, allowing us to see connections we might not have previously spotted. Then piecing these together to generate a new story.

The main critique of this approach is that it prioritises the interests of the one who holds the birds-eye-view, even if recognizing more complexity than unilinear stories. Scott has been duly criticized for this. His focus on totalitarian cities at the expense of egalitarian ones being one example. However, I am not here to be pigeon-holed into arguing against generalisation and social theory simply because none of them are perfect (In any case it would be a fallacy to believe in such a possibility). The main thing missing for me, in this bird-eye-view approach, is of a different kind.

What I believe is missing is not simply that which gets lost in any empirical game of revealing (and by extension camouflaging) different factors and a new story, whether Scott’s or anyone else’s. Instead, I believe that this birds-eye-view makes its readers and users dependents, rather than empowered by these stories, even if they aren’t so daftly reductionist.

Anti-pedagogist Ranciere argued that learning imparted through masterful birds-eye-views or ‘holistic frameworks’ creates a relationship of dependency on the masters of explication. You look up to their perspective and learn what it tells you. At the same time, whether you like it or not, you now look down to others who haven’t yet learnt this ‘more complex’ or ‘new’ perspective. It creates a ladder of less or more understanding people, with the birds-eye-view as the superior step in understanding.

“Playing with the past.”

This does not mean by any measure remaining ignorant of empirical observations, ignoring social theory or working with teachers. Quite the opposite. Instead, it means I am not interested in fighting for a new top dog perspective and bored of the work of anyone else who is. Because it is the medium of this thinking (as also expressed in pedagogical ideas of scaffolding and explication) that is problematic, rather than it simply being a question of the differing validity of the message that it holds. I think this is what a member of the Rojavan Revolution, Sarah Marsha, suggests when she notes that understanding ‘what’ is crucial, but by itself leaves you alienated from understanding ‘how’; To know in your bones, in your heart, through equitable and equal conversation. It means information not projected at you, which forces you to remain silent or to consume, but instead understanding what it means to act in the world, not simply understanding the world.

(Pre)histories become powerful parts of life when we ask: ‘what does it mean to act in (pre)history?’. History is always an action of the present. Therefore, birds-eye-visions of the past or future suffer from a utopian problem of abstracted predefinition. I would rather dialogue with the past as a way of seeing other possibilities in the present, as well as recognizing that what we are dialoguing with are historical dialogues in themselves.

Therefore, I am not interested in alternate stories or ‘identification of factors’ wrenched from the lived debates that they are embedded in. There is no true history, but there are truths and there are lived truths in seeing histories from your present position of action. Next time you have a conversation, don’t present facts, data, information, or knowledge as handed down givens floating about in some so-called objective void visited upon your listener via you — even if you packed more complexity into a new narrative. Nor simply forget empirical observation either. Remember you and the data. Present learnings about (pre)history as arising from the context they were given to you in and, in doing so, allow the debate that is the human story to teem. I believe the next book in the reading circle — ‘Roots of Civilisation’ — does precisely this.

AVI (DR KBH)

Teacher of global public health, researcher of land work systems, role player, sculpture, demon summoner, cook of many tasty things.

TO VISIT AVI’S BLOG CLICK HERE.